Wood Machining Institute, in Berkely, CA.

Wood Machining Institute

A FREE book (written by Freeborn) TO SAW HAMMERING is downloadable

here called carbide saw processing

It has a nice chapter on hammering

http://wayback.archive.org/web/*/http://www.cs4u.org/*

http://web.archive.org/web/20071116102319/http://www.cs4u.org/blades2.htm

....

cs4u.org/cleaningsawblades.htm

Carbide Saw Manual

Description: Thirty years later this book is still widely

acclaimed by true experts in the tool field. Some of the information is a

bit dated but the essential information is still accurate and clear.

Synopsis:

Lowell Freeborn is widely acclaimed as a genius in the tool

industry. He started Systi Matic with Bob Budke and then went on to

found Freeborn Tool. Among the many ways his genius manifested itself

was in his ability to make very technical issues very clear while still

being entirely accurate. His description of saw hammering is perhaps

the shortest and clearest ever written.

Product Details:

·

Paperback: 56 pages

·

Binding: Wire-O

·

Published: October 2006

http://people.musc.edu/~gormanj/Lowell%20Freeborn%20Carbide%20Saw%20Manual.pdf click to view

===============================================

foley belsaw circular saw sharpener manual

Circular saw to bandsaw (the wisconsin logging book, 1839-1939)

. same year. Automatic saw sharpeners for gang saws were offered for

sale at least as early at June 8, 1880. Circular saws, despite their

drawbacks. doing custom sawing for farmers, never had any need for more

than a circular saw, and, as time went on, a thinner saw 224. circular

saw started out small, not for sawing lumber, but for trimming and

butting lumber already sawed by the up-and-down or muley saws. added to

circular sawing with the introduction, some time in the 1870s, of the

"double saw," that is, two saws, one on.

Carbide Saw Specification Manual

Contents,

General Specifications, Saw Plates Concentricity, Outside Diameter,

Thickness, Hardness, Saw Plates Flatness, Saw Plates Runout, Saw Plates

Finish, Saw Plates Spline, Saw Plates Bore, Pin or Bolt Holes, Gullet

Profile, Saw Plates - Carbide Notch, Strob Saws Slots, Carbide Tips

Concentricity, Hardness and/or Grade, Size and Placement, Grinding,

Brazing, Strob Saws Cutters, Equipment for Quality Control. [Read More/Order]

Braze Failure Analysis, Especially Failure Analysis

This

book was originally written for a very narrow audience, those that

braze tungsten carbide for tools. However it has found wide acceptance

because of the wide use of pictures. As one reviewer in the automotive

industry pointed out, bad braze joints look the same for the same reason

no matter what the materials are. We will show you many of them and

explain how they occur and how to easily and simply fix them.

[Read More/Order]

Chisels on a Wheel (Reproduced)

Chisels

on a Wheel by Jim Effner 1992, 199 pages, 231 Illustrations, 11

Chapters, 78 topicsThis is often described as the finest book ever

written on woodworking tools and their use. It was written with the

active cooperation of over forty of the finest tool companies in the

world. The writers style is clear and it is very heavily illustrated.

This book is widely used as a training document in tool companies. It is

also very, very good for the small shop and individual woodworker. The

original book is long out of print and copies are very hard to find. It

can take months and cost up to $100 to find a copy. This is a copy of

the original reproduced with and protected under the original copyright.

[Read More/Order]

=======================================

Sawmill

http://www.oldengine.org/members/jdunmyer/sawmill/index.htmSawmill bladeTension

http://www.oldengine.org/members/jdunmyer/sawmill/sawblade.htmFilers forum

http://www.thinkerf.com/filers.htmDownload

Balance saw

http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/fputr/fputr12.pdfFormulaes on speed and kerf

http://www.thinkerf.com/Downloads/FormulaSheet.pdf----------------------------------------------------------

http://groups.google.co.in/group/rec.woodworking http://groups.google.co.in/group/rec.crafts.metalworking

================================

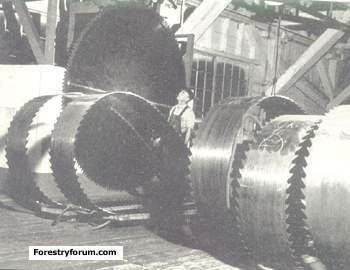

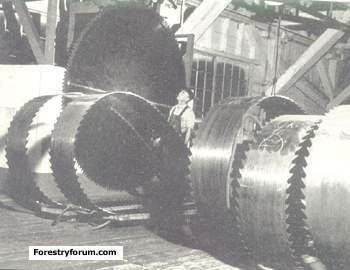

http://www.forestryforum.com/board/index.php?topic=13297.msg188718#msg188718

http://www.sawyersandfilers.org/index.htmGo to their links page and you will come up with a couple of saw doctors. Casey Cramer writes articles in the

Northern Logger

about circle saws. He seems like the kind of guy that would give you

all types of information about seminars, schools and where to get

tools.

http://www.senecasaw.com/

http://www.northeastsawfilers.com/index.phpThere are a series of books printed in 1923 (Audels carpenters and

builders guide 1 thru 4). There are 4 books in total and book 1 chapter

13 has 30 pages on circle saw blades.

------------------------------

book in pdf that is all about running a circular mill. It has a section

on hammering blades. If you would like I could send you a copy. The

book is called Circular Sawmills and Their Efficient Operation.

http://www.fpl.fs.fed.us/documnts/misc/circsaw.pdf

-----------------------------

www.leevalley.com

owwm.com

It has a section where you can find an old catalog from

American. It has lots of kool pictures and discriptions of different

parts and models. This helped me Identify my mill.

------------------------------

Re: circular saw hammering I don't think a ball peen hammer is the correct hammer for any hammer

job, not to say it wouldn't work in a pinch. There many different

kinds of hammer weights and face types, all for specific uses. I am

very consious of the safety factors having heard stories of mishaps.

------------------------------

I have purchased a $250.00 doghead hammer, a circular blade mandrel with

gauge, and a saw hammering table. Still need an anvil, a cross face

hammer, and a tensioning gauge. So as you can see, I'm trying to learn

this correctly. I am sure sawyers have done alot of things to get them

out of a bind, but from my research it gets pretty complicated

------------------------------

Guy that taught me how to saw on a Corley mill, 52" blade, hammered right on the mandrel. Tools

,

a 6# sledge with short handle, a 4# engineers hammer, a BALL PEEN, a

carpenters framing square, and a yellow keel. I forget now, just what he

was looking for, but, my saw stood at "RIGID" attention, when it got up

to speed.

I started out with a blistered 48" saw, and he

showed me exactly what was wrong, and that it would never be right

again. He hammered it to get my mill going, and we sawed for 2 weeks as

it started waving more and more.

Bought a good used blade and hammered it to fit my power, and never looked back

------------------------------

No need for a string on the

headblocks. To set the lead, loosen up your saw guides, so there isn't

any pressure on the saw. Measure the distance from the saw to the

headblock. Mark the tooth on the saw.

Move the carriage to the opposite side of the saw. Turn the saw so you are measuring on the same tooth. Measure that distance.

You want the back side to be a little longer than the front side (where the saw guides are at). Distance to start at is 1/16".

You will find that the way you file a saw has a lot to do with how the saw performs.

------------------------------

The

saw hammering class was a great success. It was about 8 hours long. The

covered everything. Had a great instructor who has been pounding saws

for a living for 32 years. There were about 30 people three, but only

two for the circular saws, everyone else was there for bandsaws. I had a

hard time taking pictures because of the Amish students. I asked about

pictures, but the Amish said they didn't want there pictures taken.

Ckeck

out the grooves wore into the test arbor from doing check thousands of

circular saws. The manilla folder is to cover the anvil for leveling

blows. It is then removed for trnsioning blows.

I never knew bandsaw had to be leveled and tensioned. They went over

everything on bands..welding, retooth,repairs, leveling and tensioning,

stelite, forging teeth, gumming and on and on. they had 200 blades there

waiting to be done. I will put more band pictures on my gallery

--------------------------------

------------------------------

I actually want to learn every detail of SAW tensioning from theoretical

and practical aspect. I am in INDIA .Woodcutting is not at all an

Industry here; like Canada , Australia / Newzeland, so expert

Sawdoctors in this field are not available.There is no sawdoctors

institute here. I am a mecanichal engineer and I have a company

producingSTEEL CUTTING CIRCULAR saws dia 1000-2200mm (40'' - 80'), thick

10mm used only in steel rolling mills. Our saws do not require

tensioning as these are machined and well ground. Our sawdoctors know

only Saw straightening or levelling by big hammer (10kg) and straight

edge/light gapping method. Now suddenly i need to learn this Saw

tensioning method for reasons described at the bottom.

1) What should be the size and shape of the hammer for tensioning a 70 inch steel saw 10 mm thick made of alloy steel..

What is the formulae you use to find out required tension in a saw?

2) How tension is measured by tension gauge in a big saw?

please name a few tension gauges.

3) How the hammer blows are appiled ? Can i use a PENCIL like tool inbetwwen the hammer and saw to increase the amount of blow.

Are hammer blows are done contimuasly in periphery or in one spot and the next on the digaonally opposite spot?

Someone told me that These saws are tensioned by small DOGFACE hammer

of 2kg on a CHILLED ANVIL ie hard anvil.

4) Is there any SAW TENSIONING HANDBOOK discussing the subject from zero?

5) Have you ever used any heat resistant Coating to reduce vibration of the saws??

6) Are there any Machine driven hammers to apply tension?

One of our customer have fixed a Computer driven Vibration meter and

they require it tensioned.Not only that they require it to be tensioned

by hand as ROLL TENSION MACHINE or STRECHING machine tensioning are

destroying the quality of blades. [blades are special heat treated

blades]

I am doing some Theoretical calculations- i need to learn

all theoretical details of the TENSIONING.I want a book which describes

the tensionig method from a theoretical and practical viewpoint from

zero .

Some of Engineering idea

Amount of Required tension depends on several aspects like

a) TEMP Gradient ASPECT 900-1500 DEGREE C

(in this case )

b) ELASTICITY aspect or tension and leveling

[elasticity includes eccentricity and Tension ]

c) Rolling machine Engineering aspect.

d) Composition of Steel to be Cut

---------------------------------

you could try

www.springerlink.com it seems they have the more technical aspect of saw tension.

saw tensioning. One hit was author R. Szymani, who is now the Director

of the Wood Machining Institute, and has a newsletter and software about

design and tensioning saw blades, circular, band, large and small.

------------------------------

hammering to a certain speed..is the amount of speed it takes to pull

the tension out of the mid radial area. As the saw gets up to speed the

rim area wants to strech do to centrifugal force. You have to prestrech

the mid radial area, so that when this happens the blade will run

straight and true.

-------------------------------my saw hammer dude.

He does roll them. And he does hammer them. And he does not do it with someone watching him, as he messes up.

He just "Goes by the feel" to get the RPM right. (what does that mean?)

Somehow,

the alchemy of hammering blades has got to yield to the science of

machines, and tools. The part of the story that I feel I have got right

is that the blades are bowl shaped, when stopped. Then, as they spin up

to RPM, they pop straight, with tension around the perimeter, held by

centrifical force.

--------------------------------

in laymans terms.. 50 years ago, the latest thing in the woods was what

we called a buzz saw. A 12 hp wisconsin mounted on a pipe frame with

bicycle wheels and handles like a horse-drawn plow. Belt drive to a 32

inch circular saw stick ing out front. the blade could be turned

vertical for bucking or horizontal for felling. Look in tom's gallery

for some pictures. The blades would eventually become unstable and shake

like a wet dog. I had a part-time job hammering these blades (for $5 a

pop). An old master millright showed me what to do, and it worked. I had

no idea why, just did what he showed me. No fancy tools, just a good

heavy flat anvil, a 5 pound hammer with a slightly curved head, a piece

of string and a piece of chalk. Lay the blade flat on the anvil and draw

a chalk line from one side straight through the center across to the

other side. repeat this 3 times evenly spaced, like cutting a pie into 8

even pieces. Use the string and chalk to draw a circle about 4 inches

in diameter around the center of the blade. Move out 3 inches and draw

another circle. Repeat the circles every 3 inches all the way out to the

teeth. Now comes the hammering. Lay the blade on the anvil and strike

the spot where the circle and the straight line intersect. 3 or 4 good

licks with a 5 lb hammer. Start at the inner circle and work all the way

around it, then move out to the next circle. When done, turn the blade

over and do the other side.

I asked the saw doc "how do I know when

I've hammered enough??" if it's not enough, the customer will bring it

back " . I have some ideas now about what this does to a blade, but I

ain't going there right now.

-----------------------------------

When the blade is stopped it should have no dishing, it should be flat [

level]. If your blade is dished it needs to be leveled. This is done on

an anvil, as stated before, only with a cushion between the anvil and

the blade. I use a piece of manilla folder. This way you are not

changing the tension with your blows. The blade must be level,

especially in the eye area, it must be perfect.

------------------------------------

In

figure #28 they are testing for the amount of tension in the midradial

area of the blade. Notice one man is lifting the edge of the blade so

that the midradil area dishes, then the saw doc is tedting for the dish.

this dish dose not show up when the saw is hung and at rest. dose that

help ?

Yup,

its helping. I was also looking at the cross-section depiction of the

blade as well as the photo in fig 28. But apparently the tension is

hammered into that area (midradial) without (before) pronounced dishing,

unless some lifting of the rim edge. Thanks, and to jdunmyer as well. ------------------------------------

I tried my hand at hammering a

saw blade or 2, without much success. Bought a tension guage &

doghead hammer, built a hammering horse, and found a suitable anvil.

But, it ain't as simple as it might appear, or surely wasn't for me. Did

have the opportunity to watch a guy who was pretty good, but that only

convinced me that I'd as soon pay someone as try to learn the art.

The

saw isn't bowl shaped, but it does drop between the center and the rim

when laying horizontal. The trick is that you lift one side, letting the

saw rest on the opposite side, and lay the tension guage at 90 degrees

to the line between your [lifting] hand and the resting point of the

saw. It will have a slight bow between the center and the rim. Test all

the way around the saw, on both sides.

The message about marking

the saw radially and with concentric circles is correct, from what I

remember, and it must be done on both sides of the plate. Hammering is

done equally on both sides, and you don't just bang away. It takes

surprisingly little work with the hammer to REALLY affect the saw, and

the hammer is nowhere near 5 pounds.

------------------------------------

About 10 years ago at the Steam-Up at Brooks Oregon, an old timer was

showing how to "hammer saw". He had a box full of gages that were for

saw diameter and saw speed. These gages were like the edge of a large

diameter circle, I would guess that they could have been 30 to 40 ft in

diameter or larger. He also had straight edges that he used to repair

saws that had been damaged before he hammered them for speed.

This

old man was very skilled in how he used the hammer, he knew just were

to hit the blade to get the correct results. I would say that it takes

years to get this kind of skill. I don't know if gages were shop made

or bought, I could see no name on them.

--------------------------------------

We are very recently using Hammers for some of our clients r

equirements.

We are using DOG HEAD, FLAT HAMMER, BALL PEENS (1 kg to 10 kg) but never use cross peen.

--------------------------------------

My 12 mm Thick saws are called cold saws/hotsaws made of

Hi-speed steels ; used in Steelplants to CUT steels.

Thick 10-12 mm

DIA 1500 mm

RPM 1400 RPM

TEMP during cutting 900 Degree C.

It is very difficult to find out the actual tension in the saw

as Tension gauze cannot be applied , as saw cannot be

bended.Sometimes we tension it with calculations with Only Ball peen

hammer and straight edge. And also we tension it with rolling machine.

I donot use a cross peen hammer. What is the actual purpose of it ?

--------------------------------------

those are some very thick sawblades!

I am surprised to learn that tension is even an issue with them. The

ones we use are for cutting wood and are only about one third of that

thickness. Many of them are of 2 to 3 times that diameter as well, so

they depend upon centrifugal force to make them run true.

A

ball-pein hammer expands the metal in all directions at once, so it is

useful in doing things like hammering a saw. A cross-pein, on the other

hand, only expands the metal in a direction perpendicular to the pein,

so it is useless in hammering saws.

Keep watching for more answers to your questions. Though we are woodworkers, a lot of people here also work with steel.

--------------------------------------

Cross peen hammers expand metal in one direction.

I understand from your comment how it is creating tension.

Hitting the rim with a cross pin hammer {presently we do it with a Small 1 kg ball peen hammer} keeping the saw on an anvil causes deformations and block marks on the rim.This pushes the material inside and causes inward tension. Marking the saw rim in this way

continuasly (ie for 1400 x 3.14 periphery 500 such markings) gives very appropriate tension for us.

I will try to develop a Cross peen tool with a slant on one side and also

not square but trapeziodal.

___

/ ___ \

Tensioning is required for Steel cutting hi speed saws as VIBRATION and NOISE takes place otherwise.

This is a sign of ill functioning and it ultimately breaks the gearbox of the machine.

It also reduces the saw life abruptly.The vibration is measured by

Computer and suitable softwares throughout while operating.

Recently we had to learn everything thing about 'Saw tensioning by hand'

,

a 6# sledge with short handle, a 4# engineers hammer, a BALL PEEN, a

carpenters framing square, and a yellow keel. I forget now, just what he

was looking for, but, my saw stood at "RIGID" attention, when it got up

to speed.

,

a 6# sledge with short handle, a 4# engineers hammer, a BALL PEEN, a

carpenters framing square, and a yellow keel. I forget now, just what he

was looking for, but, my saw stood at "RIGID" attention, when it got up

to speed.

I am surprised to learn that tension is even an issue with them. The

ones we use are for cutting wood and are only about one third of that

thickness. Many of them are of 2 to 3 times that diameter as well, so

they depend upon centrifugal force to make them run true.

I am surprised to learn that tension is even an issue with them. The

ones we use are for cutting wood and are only about one third of that

thickness. Many of them are of 2 to 3 times that diameter as well, so

they depend upon centrifugal force to make them run true.